|

Morton FELDMAN (1926-1987) - Crippled Symmetry (1983)

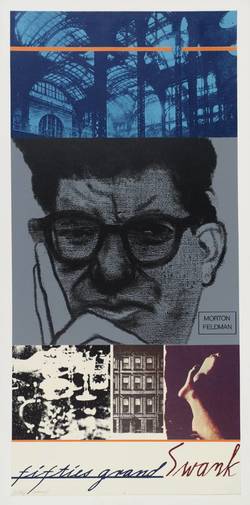

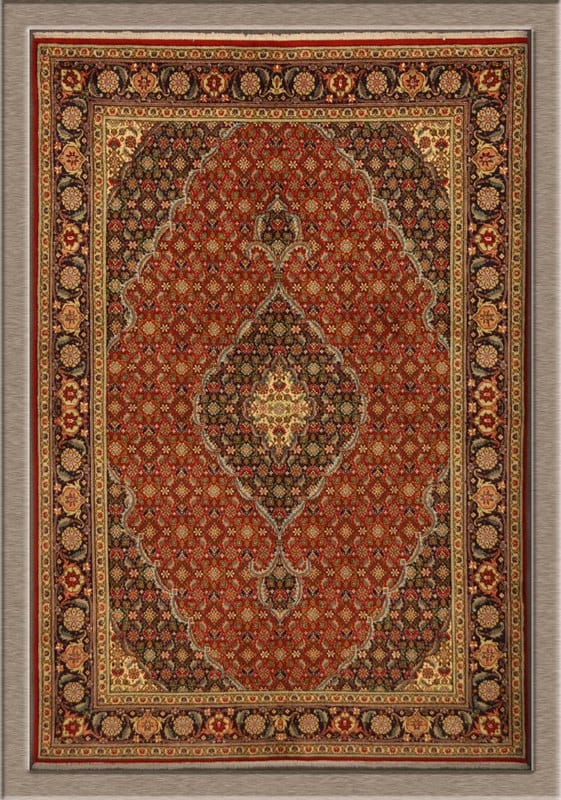

“Proust knew what it was all about. The whole lesson of Proust is not to look for experiences in the object, but within ourselves.” ~ Morton Feldman I am not sure how other people conceive of important past moments in their lives, but mine come in snapshots simultaneously nebulous and vivid. In my first semester at SUNY Buffalo, I remember with perfect precision looking over my right shoulder at a two-story vitrine replete with iconic posters from new music festivals from the past few decades. The focal point of all of these intriguing posters was a print of R.B. Kitaj’s “Fifties Grand Swank,” in which the artist placed a charcoal portrait of a pensive looking man with thick glasses next to images of train station ceilings and photographically overexposed feet. The man in the poster, I later discovered, was a composer named Morton Feldman. Despite the fact that I didn’t know who this was at the beginning of my studies, I - not knowing why - adopted this poster immediately as a sort of talisman, encouraging me to work hard, to absorb everything I could, and telling me when it was time to call it a day on during marathon practice sessions lasting until dawn. Little by little, I uncovered the deep history of my surroundings in the music building at SUNY Buffalo. I found instruments in the percussion cabinets that had been chosen by John Cage. I learned that the five small circles coarsely outlined in pencil on a gong were the fingerprints of Iannis Xenakis, who had attempted to isolate specific overtones in 1976. And I discovered the immense legacy of Morton Feldman, who taught composition at SUNY Buffalo (after tricking Lukas Foss into hiring him) from 1973 until his death in 1987. The subtitle to Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo is “how one becomes what one is.” For me, discovering Feldman as a young man felt like discovering a cultural prism: In reading essays and interviews with him, I felt I would shine my light toward the composer, and that light would be refracted in every direction. Through Feldman, in the realm of painting, I discovered Pollock, Rothko, Guston, Sekula, De Kooning and Vermeer. In the realm of literature and philosophy, I discovered Stendhal, Kierkegaard, Kafka, O’Hara and Beckett. In the realm of music, I discovered Varèse, Webern, Scriabin, Takemitsu, Schubert and Josquin. In the realm of pop culture, he led me to study the elegance of Frank Sinatra and Fred Astaire. I see traces of his fingerprints on virtually everything I am interested in today. * * * Feldman’s early works, like the percussion solo King of Denmark, were studies in indeterminate compositional language. His middle period, beginning with Madame Press Died Today At Ninety (1970), marked a newfound interest in concrete notation. Feldman’s late period (beginning around 1978) is characterized by works of extended duration, ranging from thirty minutes to six hours. Throughout the composer’s vast catalogue, the unifying themes are those of slowness and quietude, qualities John Cage first described as “heroic,” and later as “erotic.” Crippled Symmetry (1983) for flutes, piano/celesta and percussion, belongs to Feldman’s late period, but contains elements of the previous two. Clocking in at about ninety minutes, the individual instrumental parts are explicitly notated, but the coordination of the parts is left up to chance. Similar to the way a Calder mobile constantly arrives at unpredicted new formations, and yet remains unmistakably Calder’s, Crippled Symmetry unfolds differently with every performance, and yet at all times belongs distinctly to Feldman. In photos of Feldman, one can clearly see that whenever the composer is beholding a work of art (whether a Rauschenberg painting, an ancient frieze or one of his beloved Middle Eastern carpets), he is not simply looking at the object in question, but rather examining it, his nose practically pressed against the thing he is studying. This may be attributable to an inquisitive mind, but it is also likely that it had something to do with Feldman’s extreme myopia. Of the many different explanations for the way that Crippled Symmetry functions formally, I found one from percussionist Jan Williams compelling: Feldman’s eyesight was ostensibly so bad that he wanted to be able to read and perform his own part at the piano and avoid coordinating cues visually with other members of the ensemble. Hence: three independent solos. The title Crippled Symmetry makes reference to the patterning on 19th century nomadic, oriental carpets, particularly those of Turkey. Feldman was astonished by the feats of memory of the female rug-makers of this tradition, comparing the repertoire of designs these rug-makers would have carried around in their heads to “learning all the works of Chopin and the thirty-two Beethoven sonatas by rote.” Feldman was captivated by the details of these rugs; what at first glance appears to be perfect symmetry, is later discovered to be subtle, masterful variations on a theme. When Feldman, who collected these carpets, would show them to friends, he would enthusiastically point out these details and say, “look at the move she made here!” During the course of Crippled Symmetry, Feldman writes simple patterns which seem to repeat, but are in actuality always artfully expanding and contracting, giving the impression (as in his beloved rugs) of repetition, when in fact they are protean. This approach to repetition, to paraphrase Roland Barthes, inflects the same notes in ways that are forever changing, constantly endowing that which is repeated with new love. * * * In an interview with Walter Zimmermann in 1975, Feldman said, “for me, sound was the hero, and it still is. I feel that I’m subservient. I feel that I listen to my sounds, and I do what they tell me, not what I tell them. Because I owe my life to these sounds. Right? They gave me a life.” Feldman’s late works, and for me in particular Crippled Symmetry, always seem to me like love letters to the idea of sound. In the same interview, he states that “sound is perhaps dead...Maybe sound just dropped dead, or will drop dead with me, or will drop dead with Cage. Anyway, it was a marvelous period as long as it lasted. For the first time in history, sound was free.” |